The impact of climate on the biota of an area can be manifested in a number of ways. One possible effect of global warming and climate change in general is that the growing season could be extended. We can measure temperature changes easily enough but the effect of the temperature changes may not be immediately apparent.

The impact of climate on the biota of an area can be manifested in a number of ways. One possible effect of global warming and climate change in general is that the growing season could be extended. We can measure temperature changes easily enough but the effect of the temperature changes may not be immediately apparent.  In part, this is because the changes will be gradual and small but changes are obscured by annual and daily variations. One means of assessing the long-term influence of climate changes is to follow the phenological changes in the flora. This could include such things as documenting the dates of first flowers (anthesis) or bud breaks of tree leaves. In the present investigation, we have chosen to record the dates when open or viable flowers are still present on plants in the area late into the season. This can be taken as one measure of a late growing season. It is not possible to know the exact date when an individual flower is no longer viable. In reality, the probability that the late-flowering blooms could be fertilized and go on to produce seed is rather low; however, the monitoring of such flowers over a period of time should provide a measure of the change in growing season dates.

In part, this is because the changes will be gradual and small but changes are obscured by annual and daily variations. One means of assessing the long-term influence of climate changes is to follow the phenological changes in the flora. This could include such things as documenting the dates of first flowers (anthesis) or bud breaks of tree leaves. In the present investigation, we have chosen to record the dates when open or viable flowers are still present on plants in the area late into the season. This can be taken as one measure of a late growing season. It is not possible to know the exact date when an individual flower is no longer viable. In reality, the probability that the late-flowering blooms could be fertilized and go on to produce seed is rather low; however, the monitoring of such flowers over a period of time should provide a measure of the change in growing season dates.

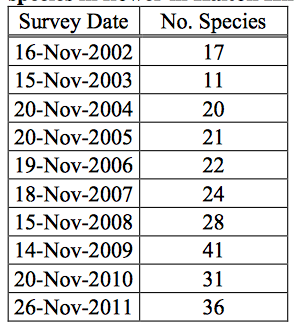

Each autumn from 2002 until 2011, members of the Halton/North Peel Naturalist Club have conducted a survey of the plants still in flower in the latter part of November. The exact dates of the survey are indicated in Table 1. The dates ranged between November 14 and November 26. The exact locations of the survey have changed somewhat each year; however, the Willow Park Ecology Centre and the Lucy Maude Montgomery Garden in Norval have been checked every year. In the earlier years, the woods near the Georgetown Fair Grounds were examined while more recently the survey route included the Dominion Seed House Park. As well, incidental observations of flowering plants in parts of Georgetown have been added to the list.

Species observed still flowering on the survey dates are included in Table 2. The number of species in flower observed has fluctuated from year to year (Figure 1) but there is general trend to larger numbers over time. In part, the trend might have been influenced by the choice of sites visited; however, other factors such as site management at Willow Park and natural succession of species within an area likely played a mitigating role as well. Overall, the survey documented as few as 11 species still in bloom in 2003 and as high as 41 in 2009.

The vast majority of the 108 species on the list (Table 2) are cultivated garden species along with several species generally regarded as introduced weeds. The cultivated garden species includes several that are native species that have been purposely planted. Only about 10% of the species on the list are ones that are both native and endemic to the area. Only two species, Canada Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) and Common Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) were found flowering every year. Other commonly encountered species (6 to 8 years each) were Yellow Chamomile (Anthemis tinctoria), Calendula (Calendula officinalis), Garden Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum hybrid sp.), Wormseed Mustard (Erysimum chieranthoides), Scentless Chamomile (Matricaria perforata), Canker Rose (Rosa canina), Common Groundsel (Senecio vulgaris), Tall White Aster (Symphyotrichum lanceolatum), and New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae- angliae). Interestingly, all of the species on the most common list except for the Wormseed Mustard and the rose are members of the composite family.

A survey of this type on its own cannot be expected to demonstrate that climate change is having a significant impact on the length of the growing season. In combination with many other surveys though, the data set will be more robust in demonstrating that a change is indeed occurring. This effort is a small contribution towards that end.

by W.D. McIlveen

Halton/North Peel Naturalist Club