Attention: Jill Van Niekerk, Superintendent of Forks of the Credit Provincial Park

Forks of the Credit Provincial Park contains many hectares of old field habitat, resulting from the abandonment of agricultural land. These expansive meadows provide habitat to a diversity of flora and fauna including a number of species at risk.

Meadowlarks (threatened) nest here. Bobolinks (threatened) use the extensive old field habitat for foraging before fall migration. Bank Swallows (threatened), nest in adjacent quarry operations and forage over the meadows. Monarch butterflies (special concern) lay eggs on the abundant milkweed and nectar on the profusion of asters, goldenrods and other old field wildflowers.

Beyond these species at risk are a number of plants and birds at FCPP that are locally uncommon. Among the plants are Hoary Vervain (Verbena stricta), Foxglove Beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis) and Amethyst Aster (Symphyotrichum x amethystinus). Locally uncommon birds, supported by the old field habitat, include clay-colored sparrow and orchard oriole.

According to Biodiversity in Ontario’s Greenbelt, a document released by The David Suzuki Foundation and Ontario Nature in November 2011, “only 441 hectares of the Greenbelt is covered by grasslands – far less than one per cent of the entire plan area.” The Nature Conservancy of Canada states that “Grassland bird species have shown steeper, more geographically widespread and more consistent decline than any other category of North American species.”

According to the Bobolink and Meadowlark Recovery Strategy prepared by the Government of Ontario in 2013 “Over the most recent ten year period, it is estimated that the Bobolink population has declined by an annual average rate of 4% which corresponds to a cumulative loss of 33%. Over the same period Eastern Meadowlark populations have declined at an average annual rate of 2.9% (cumulative loss of 25%).”

Although various factors are responsible for these declines, the loss of old field and grassland habitat in Ontario is widely acknowledged to be one of the major drivers.

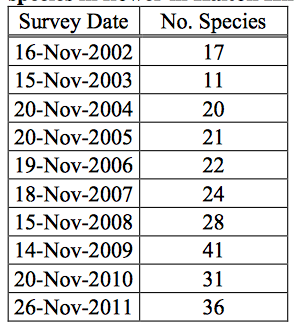

FCPP is gradually reverting to woodland. Over three decades of observation by HNPN club members, this transition has been very evident. Without human intervention, the ecologically valuable old field habitat and the diverse flora and fauna that it supports, will eventually be lost.

Our club recognizes that species diversity depends in large part on habitat diversity. We are supportive of the maintenance of a mosaic of habitats at FCPP. Extensive forest in the valley of the Credit River should clearly be protected. The current meadowlands merit protection as well, which will necessarily entail some measure of active landscape management. Areas of shrubby growth – also very important habitat – should be maintained as well.

The Forks of the Credit Provincial Park Management Plan published in 1990 by the then Ministry of Natural Resources (Now Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry) appears aligned with the concerns of the Halton/North Peel Naturalist Club. Article 3.0 reads: The goal of Forks of the Credit Provincial Park is to protect the park’s outstanding natural, cultural and recreational environments and to provide a variety of outdoor recreation opportunities. The existing old field habitat has both natural and cultural value.

A specific protection objective of the FCPP management plan (Article 4.1) is to protect the park’s six species of vascular plants which are regionally rare. Only one of these plants – Aster pilosus – is listed in the management plan, but the other five may include other plants that depend on open meadow habitat to grow.

The Forks of the Credit Management Plan also includes a commitment for managing a portion of the upland meadow complex as open landscape. An entry under Vegetation Management (Article 7.2) reads: The vegetation of the field in the Natural Environment Zone in the eastern plateau will be managed (i.e., periodic mowing and/or burning) to maintain the open character of this rolling landscape. Care must be taken to protect a representative portion of the old field succession, for interpretive purposes as well as to maintain the regionally rare plant, Aster pilosus.

As cited earlier there are several other significant species of plants, birds and insects, also dependent on the old field habitat of FCPP, that merit protection. The Halton/North Peel Naturalist Club calls on Ontario Parks to act on the provisions of article 7.2. to maintain this old field habitat.

With Forks of the Credit Provincial Park there is an opportunity to help conserve a significant expanse of old field habitat that is critical to the future of at-risk species. There is an opportunity as well to educate users through interpretive initiatives (signs, display boards, publications) about the critical importance of grasslands and old field habitat for biodiversity.

With respect,

Don Scallen,

President, Halton/North Peel Naturalist Club

RELATED: Grand River Conservation Authority “Grassland for bobolinks in the central Grand”